The policy argument for balancing modernization, operational efficiency, and equitable access

We’ve said it before, and we’ll say it again: Transit agencies must continue accepting cash at the farebox as a fare payment option. Cash acceptance is a core access feature for transit-dependent riders, a resilience feature for all riders, and, when paired with modern cash-to-digital pathways, a practical bridge to the benefits of account-based and open-loop fare systems.

While cashless fare collection systems are growing in popularity, the evidence shows that eliminating cash often shifts costs and burdens to riders, requires a sizable investment in replacement infrastructure, and can trigger equity concerns that undermine public trust and ridership. A best practice approach is to expand options for riders through modern payment platforms while maintaining the ability to pay for transit with cash.

The core policy issue: Mobility for everyone, not only the digitally enabled

Public transit is essential infrastructure. In 2024, U.S. transit operators reported providing 7.6 billion passenger trips, carrying roughly 38.1 billion passenger miles, and operating in 502 urbanized areas, according to FTA’s National Transit Database. That scale matters: Even small barriers to paying a fare can translate into large real-world impacts such as missed work and medical appointments, skipped school, and difficulty completing basic errands, especially for riders with the fewest alternatives.

Cash acceptance directly supports equitable mobility, a fare system design philosophy that aims to eliminate barriers while modernizing payment options. Genfare’s Achieving Equitable Mobility white paper states plainly: “Continuing to accept cash and coin at the farebox is essential for equitable mobility.”

Choice riders vs. transit-dependent riders: Why “one size fits all” fails

Modern fare tools (e.g. tap-to-pay, mobile wallets, account-based ticketing) are attractive for choice riders — people who can drive, use rideshare, or avoid travel if transit is inconvenient. These tools can reduce friction, speed boarding, and improve the overall rider experience. But fare policy must also work for transit-dependent riders, including those who are unbanked, underbanked, cash-based, or digitally constrained.

The FDIC’s 2023 national survey found:

- 4.2 percent of U.S. households (about 5.6 million) were unbanked.

- 14.2 percent of U.S. households (about 19.0 million) were underbanked.

- 66.2 percent of unbanked households relied entirely on cash.

Even beyond banking status, cash remains common in daily life. The Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta’s 2024 Survey and Diary of Consumer Payment Choice reported that 83 percent of consumers used cash in the prior 30 days and that cash remained a meaningful share of payments.

The implication is that if a transit agency removes cash, it is not merely changing a payment channel, it is changing who can ride without added friction.

Disputing the “hidden costs of cash at the farebox” narrative: What it gets right, and what it misses

A common argument is that cash slows boarding, increases labor and logistics costs, creates security risks, and increases hardware maintenance burdens. A recent article on the APTA Knowledge Hub claims “massive cost savings” from reducing or eliminating cash and suggests digital fare handling can be “more than three times more efficient than cash.” While there are significant benefits to open and digital payment platforms, the article overreaches in its conclusions for four reasons:

Dwell time is driven by operations, not just payment media

Fare collection can contribute to increased dwell time, but those delays are often the result of riders who are unaware of how or what to pay. Payment platforms that allow riders to pay with whatever form of payment is in their pocket reduce confusion at the farebox, speeding boarding.

Cashless fare collection can introduce friction in other ways (e.g. declines, app outages, and account issues) that doesn’t show up in simple dwell-time comparisons. Plus, there are better ways to reduce dwell time, including all-door boarding, stop optimization, headway management, and signal priority, especially for bus routes operating in mixed traffic.

Cashless systems create new recurring costs (and new failure modes)

The cost-of-cash argument often emphasizes counting, vaulting, and armored services but underweights the costs of cashless systems:

- Payment processing fees

- Vendor support

- TVM purchase, maintenance, and operation

- Cybersecurity

- Device lifecycle replacement

- Customer service for accounts/refunds/chargebacks

- Maintaining reload and distribution networks

This means going cashless doesn’t necessarily reduce the overall cost of fare collection, but rather shifts costs from one accounting classification to another.

Thoughtful transition workarounds can increase friction for cash-dependent riders

Some argue that cash-dependent riders or unbanked/underbanked riders can obtain digital status through off-board cash loading and on-board cash digitization. In practice, off-board conversion can mean extra trips, limited business hours, and added fees; on-board digitization can add operator burden.

Why are we asking those most dependent on transit to get to work, health care, or school to make additional inconvenient trips so they can pay to ride transit?

Equity risk is not hypothetical; agencies have reversed cashless pilots

Omnitrans’ cashless fare analysis, described below, highlights real-world backlash: Santa Monica’s Big Blue Bus implemented a one-year no cash onboard pilot (TAP-only). While it saw dwell time improvement, two-thirds of customers favored restoring cash, and equity concerns negatively impacted the project, leading the agency to return to cash.

What the field evidence shows: Omnitrans case study

Omnitrans’ analysis provides a concrete example of why eliminating cash can be difficult, costly, and disruptive:

- Cash is a large share of boardings: Omnitrans reports 32 percent of fixed-route boardings paid with cash and 40 percent or more for microtransit; their peer comparison shows similarly high cash shares for large agencies.

- Cashless requires major replacement infrastructure: Omnitrans estimates a cashless transition would require adding approximately 200 pass outlets and ticket vending machines, noting that only 2 percent of the service area is currently covered by outlets.

- Upfront costs can be significant: Omnitrans’ early estimate shows $12 million for TVMs.

- Cashless may still require “cash-era” services and add new costs: Their needs comparison shows cashless systems still requiring armored services and often-increased banking fees, plus additional staff and expanded outlet and TVM networks.

This aligns with a key policy insight: Cash elimination rarely removes cost. It instead often moves cost — and inconvenience — from the agency to riders and to new vendors and processing structures.

A better framework: Equitable mobility + modernization

Genfare’s equitable mobility framework argues the goal is to accept whatever is in the rider’s pocket — bank card, mobile, smart card, or cash — without making riders jump through hoops.

The first pillar of equitable mobility emphasizes using fare data to understand where cash is most used and to deploy targeted tools to help riders digitize cash. Importantly, this approach recognizes a practical “both/and” reality:

- Keep cash acceptance to protect access.

- Reduce agency burden by making it easier for cash riders to digitize cash (retail reload networks and community-centered locations) so they can access reduced fares, fare capping, and other structures that save them money.

Recommendations: A practical path forward

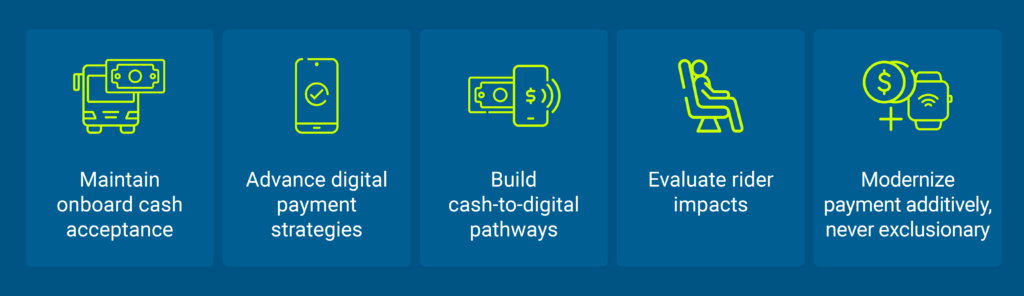

Genfare takes a firm policy stance: Cash must always be an acceptable form of fare payment. It also calls on FTA to update Title VI guidance so federally funded agencies remain “able and willing to accept cash” without placing additional restrictions on cash users. In summary, transit agencies should:

- Maintain onboard cash acceptance as a baseline access policy. Cash is a necessary payment method for a meaningful share of riders and remains foundational to equitable mobility.

- Look to advance modern open-loop digital payment strategies without excluding riders. Expand open-loop/contactless payments and mobile ticketing to serve choice riders while preserving cash as a universally available option.

- Build strong cash-to-digital pathways where cash use is concentrated. Use ridership and fare data to deploy retail point-of-sale reload options and community-accessible locations near stops so riders can digitize cash without special trips. But do not require such media to pay for transit.

- Avoid equity backlash by evaluating rider impacts before restricting payment options. Omnitrans’ findings (e.g. high cash shares, major infrastructure needs, and documented equity concerns in peer pilots) show why cashless can fail even when it improves dwell time.

- Treat payment modernization as additive, never exclusionary. Modernization should expand choice, improve reliability, and increase access, not create a two-tier system that prioritizes convenience for some while raising barriers for others.

Conclusion

Transit agencies can modernize fare collection and still preserve universal access. The strongest policy is not cash forever or cashless now, but cash-light with equity protections: Keep cash acceptance to ensure everyone can ride while investing in targeted, neighborhood-based tools that allow riders to digitize cash and benefit from modern fare policies.

This approach directly addresses the operational concerns raised in cashless advocacy pieces while avoiding the real equity, infrastructure, and public trust risks demonstrated in agency case studies.